Building a Primitive Shelter Without Familiar Materials

The sun dipped lower behind the far ridge, casting long amber shadows across the grasslands. Ragnar stood at the edge of a copse, unfamiliar trees clustered before him, broad-leaved and thick, not like the pines and firs he had known. The air was drier here, the light softer, but still the land whispered of challenge. He had no map, no kin, only tools and instinct.

He had walked for hours. The horizon never seemed to near. His feet ached from the strange ground—flat but uneven, packed with a coarse mix of rock and soil that reminded him more of dried riverbeds than forest paths. He needed shelter. Night would come, and with it, cold.

Back home, he’d have looked for birch. Its bark was light and easy to peel, perfect for wrapping or fire-starting. But there were no birch trees here. The bark on these trees was tough, fibrous, dark. He pressed his fingers against one trunk and scraped a thumb’s width. It flaked away in strips. Usable, but not ideal.

He moved further inward. The clearing narrowed. A ridge of small stone outcrops rose nearby, catching the last of the sunlight. Behind them, the land sloped downward into a slight hollow. He crouched, sniffed the wind. Still, dry. He could make camp here—hidden from sight, shielded from wind.

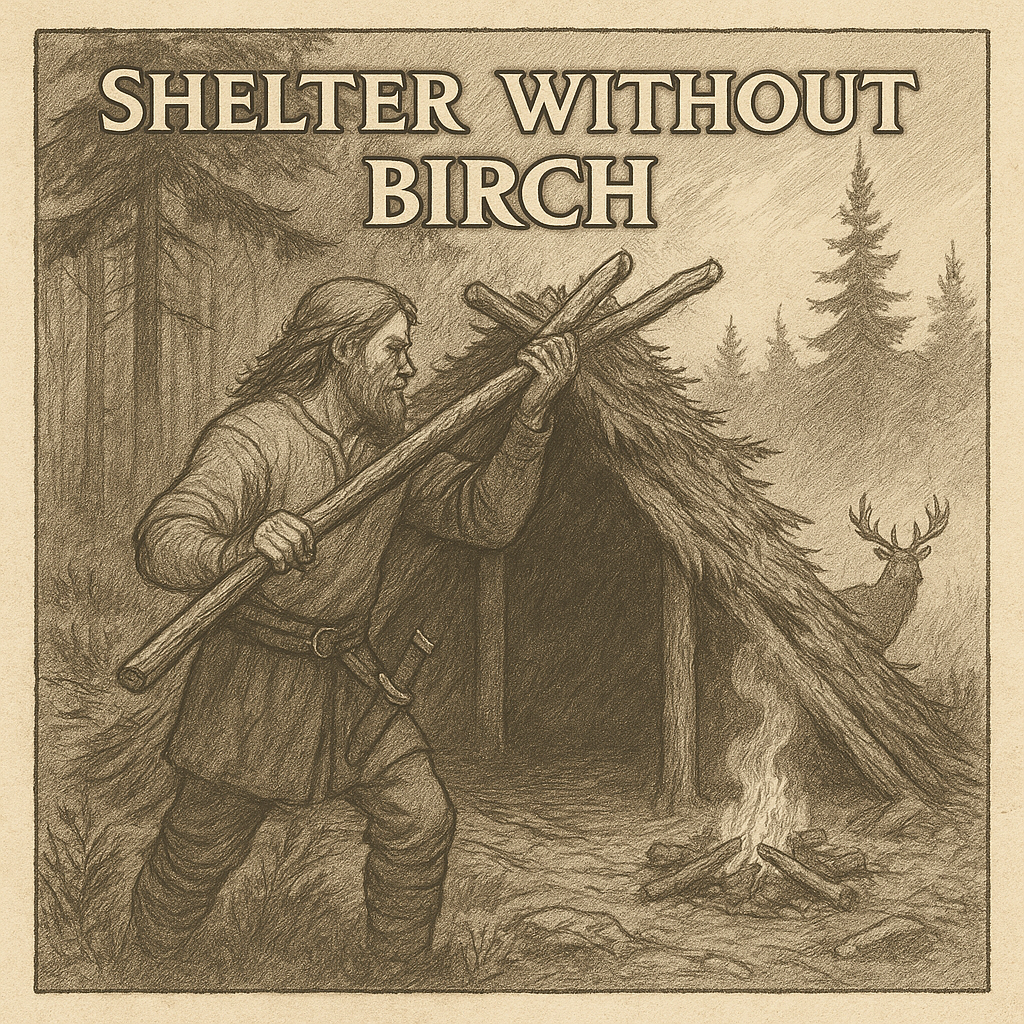

His axe came free with ease. The haft was worn smooth from years of grip. He selected small saplings first, testing their strength before cutting. These would form the frame. He worked methodically, carving notches and fitting limbs together into a simple A-frame. The longer branches he set at angles, then lashed them with thin bark strips. It would not last long—but it would last the night.

As the frame took shape, he gathered the fibrous bark and rubbed it between his palms to loosen the strands. It felt strange—coarser than he preferred—but it would insulate if packed thick. For cover, he layered it like thatch, then wove long grass and small leafy branches to block gaps. Not elegant, but serviceable.

He sat back on his heels, eyeing the shelter. It leaned slightly to one side, but it stood. It had taken him longer than expected. His breath came heavier now, not from exhaustion but from the realization of what it meant to survive alone in a strange land. He could not rely on memory. He would need to learn again.

Fire came next.

He had his flint and steel, and tinder still dry in the whale bone tube. The wind made it fussy—kept blowing the first sparks sideways. He turned his body to shield the flame. After several tries, the dry moss caught. He fed it shavings, then twigs, until a small fire took hold. Its warmth crawled across his hands like a familiar friend.

Night crept in, slow and wide. The sky turned copper, then deepened to slate. Stars began to pierce the dark. Different stars. The constellations here were foreign—tilted and skewed from what he knew. Yet the fire burned, and the shelter held.

He sat beside the flames, sharpening his seax on a flat stone. The rhythm of steel against grit soothed his thoughts.

“I will learn this place,” he murmured, not in prayer, but in promise.

Somewhere far off, a coyote yipped. Ragnar did not flinch.

He pulled the cloak tighter, slid the seax beside him, and rested beneath the angled roof of bark and branch. Not the longhouse, not the fjord, but a start.

He would wake with the sun. And when he did, he would find water.